4562 ENRIGHT

Commissioned by the Pulitzer Arts Foundation

with Kristin Fleischmann Brewer, curator and Sophie Lipman, project manager and community organizer.

Photos : raumlaborberlin and Alise O‘ Brien

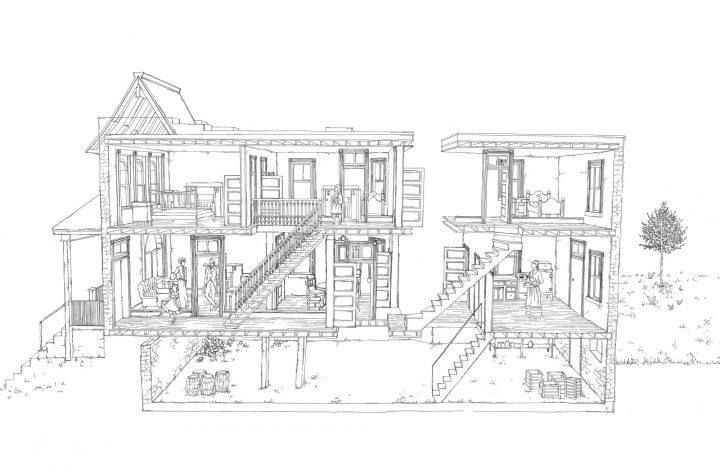

An abandoned house at 4562 Enright Avenue in Lewis Place, St. Louis was dismantled and reconstructed inside the Pulitzer Arts Foundation by raumlaborberlin in the summer of 2016. Similar to the act of rebuilding a crashed airplane, this process was also one of reconstructing the larger socio-political forces that brought about the deterioration of a neighborhood.

The project started off as an archeological study of layers containing history and traces of the building’s inhabitants, but with time it turned into a socio-political diagram of the rise and fall of the entire town. Superficially we were contesting the dream of the single-family home. However, the more we investigated, the clearer it became that failed politics and racist prejudices were the driving force behind the fatal urban dynamic we were confronted with.

“Through design research, raumlaborberlin and the Pultizer formed deep relationships with local partners to explore housing policy and demolition at an intimate level. Residents on Enright Avenue and in the greater neighborhood, stakeholders in urban planning and policy, and area demolition and re-fabrication experts gathered for informal conversations, potlucks, and block meetings, and became key advisors on the process.”

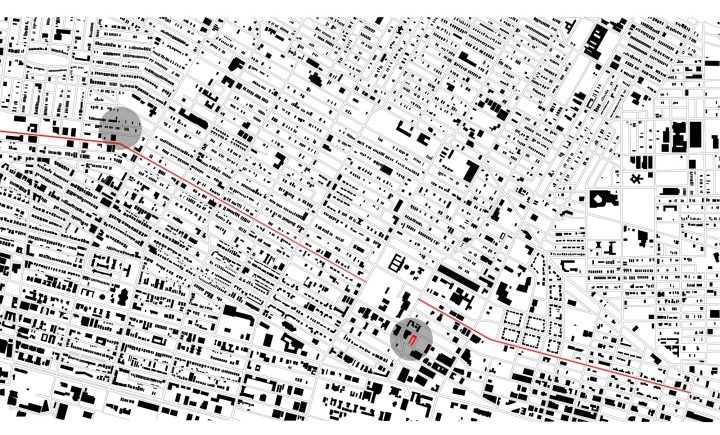

Enright Neighborhood

“Standing on the grass lot that sits directly east of 4562 Enright Avenue, where two homes were taken down after a tornado in 2011, one can look north and south to see the disparity in the treatment of the built environment. Swaths of green land open north tracing a path of disinvestment exaggerated by the path of the tornado, and to the south the glitter of stained-glass church windows and density are visual indications of public and private investment.”

Our chosen house lies in Lewis Place—a tight-knit, largely African-American community: everyone knows their neighbor, people get together for barbecues, and child-care is a communal responsibility. Residents are working hard to shift the perception of their neighborhood “north of the Delmar Divide” that has suffered almost a century of stigmatization.

The Delmar Divide

“This stretch of Enright Avenue sits one block north of Delmar Boulevard, a street known as a dividing line that shows the harsh reality of living in a historically segregated city: people living in the 63113 area codes north of Delmar are 98% African American, and people living in the 63108 area codes south are 73% white. Other distinct differences across the divide include median home values of $73,000 versus $335,000, median incomes $18,000 versus $50,000, and the percentage of residents with Bachelor’s degrees are 10%, versus 70%.”

In the South are neatly trimmed gardens, upscale cafés, and craft beer. In the north: deserted buildings, deterioration, liquor-stores and drug dealers.

Redlining is the official term for this city development strategy, aiming to prevent white flight—the collective migration of the white middle class. Obviously unsuccessful, the result is a city without any tax revenue, suffering institutions and social services.

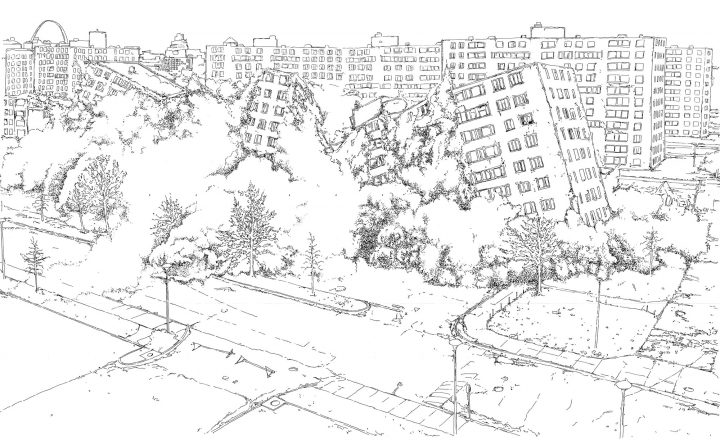

Pruitt Igoe

A failed social housing settlement, Pruitt-Igoe was famously demolished in the mid-1970’s, at twenty years old. The footage of its demolition is iconic, symbolizing the failure of mid-century urban planning, and, according to cultural historian Charles Jencks, the beginning of the end of modernity.

In 1950, overcrowded and in disrepair, St. Louis commissioned the design of the high-rise, high-density public housing complex, to be constructed in place of existing slums in the inner city. Shortly after its completion, the practice of segregation on which it was designed was outlawed. Henceforth the settlement was left largely to itself with little municipal investment in infrastructure, maintenance, or repairs, and in combination with its poor construction quality, spatial inadequacies and flawed political organization, Pruitt-Igoe collapsed into a slum arguably worse than the one upon which it was built.

Enright 4562

Our house on Enright Avenue tells a similar story. Entering from the missing porch whose imprint is still engraved on the facade, to the right are stairs ascending to the bedrooms. In the dining room a large built-in cupboard opens to both sides, serving to pass meals from the kitchen. At the end of the corridor the exterior wall has crumbled away, opening onto what was once a garden. Another door at the rear of the building houses a steep staircase that leads to a small servants’ quarter upstairs, effectively separating the privileged and poor, white and black. The same modernist philosophy of segregation and utopian planning that caused the demise of Pruitt-Igoe and Lewis Place also, albeit at a smaller scale, is responsible for the destruction of this domestic realm. And in the same way that images of Pruitt-Igoe’s demolition serve as a testament to the failure of the systems and ideas that birthed the project in the first place, our reconstruction of 4562 Enright Avenue is a thesis criticizing the same ideas and processes that still pervade many aspects of our urban domain.

Home sweet home

It was important for us to engage with the neighborhood that was the subject of our studies, so we visited Lewis Place and spoke with residents. We wanted to know what “home” means to them, what their dreams are for the neighborhood’s future, and how these wishes vary across the Delmar Divide: does everyone dream of a private home with neat flowerbeds in the front garden and a clean street? Our investigations resulted in a short film—we found that despite the rigid social divide, desires of “home” are largely universal.

© 2016 Alise O‘ Brien Photography courtesy Pulitzer Arts Foundation

The exhibition

The abandoned 4562 Enright Avenue, transplanted into Tadao Ando’s pristine Pulitzer Arts Foundation, reflects on a city full of cracks and scars. Together with the wonderful team of the Pulitzer Arts Foundation we created an exchange and dialog between two worlds that don’t often meet.

For the exhibition opening there were actually two houses. The first being the reconstruction of the interior, with windows and doors in a spatial framework representing the volume of the original building. The second house is the empty masonry shell on the Enright Avenue that was deconstructed brick by brick throughout the exhibition. The two houses were in conversation with one another throughout its duration.

Many residents of Lewis Place visited the museum for the first time when they attended the opening. In this way we managed to subvert the discriminatory urban policies that still resonate today, by engaging a demographic whose exclusion from such cultural institutions was the cornerstone of our project.

* Quotes from a text by Kristin Fleischmann Brewer/Curator at Pulitzer Arts Foundation